1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

Theobald Böhm's comment on the open G sharp key

by Ludwig Böhm (2014)

In 1981, 5 letters of Theobald Böhm to Wilhelm Popp appeared in Sweden by the aid of my research ad in a music journal, which are today in the Munich Municipal Archives, Estate Theobald Böhm I. In his letter of 5th February 1865, Theobald Böhm discussed in detail the open and closed G sharp key (original in German). The paper enclosed with that letter contains the short version of Theobald Böhm’s article on the G sharp key. Soon after, he wrote a little more detailed version which still exists as rough copy (Bayerische Staatsbibliothek, Munich) and fair copy (Library of Congress, Washington) and which he himself translated into English (Bayerische Staatsbibliothek, Munich) and into French (Stadtarchiv, Munich). Nothing was published, but the matter was treated once more in his book “The Flute and Flute-Playing in acoustical, technical and artistic Aspects”, Munich 1871, translated and annotated by Dayton C. Miller, Cleveland 1922, p. 62–71.

1) Letter from Theobald Böhm to Wilhelm Popp

Munich, 5th February 1865

Dear Sir,

You were right to recommend a flute from me and not from Lot in Paris, because my completely logical key system was only made worse in acoustical and mechanical respect by the first flautist Dorus in Paris who made a so-called improvement by a closed G sharp key. After long consideration, I have made a simple open G sharp key, because all keys of my flute from E1 upwards correspond to the natural movement of the fingers as they are closed and opened by the fingers. Dorus thought to make the new flute more accessible to players on the old flute by making a closed G sharp key as they were accustomed, but he didn’t consider that he thus got more disadvantages than advantages.

Lot had made this for him combining the G sharp key with the A key. So you get G by pressing down the ring finger of the left hand, as on the old flute, and to get G sharp you have to press up the G sharp key with the little finger, as on the old flute. However the consequence was, that both tones, G and G sharp, are pro-duced as on the old flute, whereas in my system, the G is made by closing the G sharp key with the little fin-ger and the G sharp is made by lifting this finger. I made it so after long consideration and everybody, who thinks the matter over, has to agree with me.

Dorus himself had to confess that he had made a foolish mistake when I explained the matter to him and I also made a foolish mistake for Dorus’ sake, because I didn’t immediately at this time explain publicly the inappropriateness of the closed G sharp. As Dorus was already the first flautist in Paris, of course all his pu-pils adopted the flute as he played it. But many accustomed themselves later to the open G sharp and even De Vroye told me, when I explained the matter to him last year, that he was sorry not to be able to make an-other change, because he would of course have to study thoroughly once more for some time. But as De Vroye now doubtlessly intends to sell flutes with closed G sharp in Germany, because he gets more commis-sion from Lot than from me, I’ll most probably explain the matter publicly in the near future. Up to now, I haven’t considered it worth while, because in Germany, England, Russia and almost everywhere with the exception of France, all flute players only play according to my system. On the paper enclosed, you will find an explanation of the advantages and disadvantages and you will doubtlessly accept the correctness of my explanations.

Yours sincerely,

Th. Boehm.

2) Article by Theobald Böhm (version in Washington): Remarks on the alteration made in Paris on the key-system of the so-called “Boehm Flute”.

The requirements of a good flute are first the acoustic perfection in tone and tuning, ease in playing and simplicity of the key-mechanism. Whether and in how far these requirements can be better obtained by an open or closed G sharp key is a question which will be certainly of interest for all who play or want to learn to play the Boehm flute.

1. The acoustics of the instrument

By the combination of a closed G sharp key with the open A key, the ninth or A hole can never be opened alone and as the eighth or G sharp hole is placed too far down on the flute to be able to serve the high E3 as sound hole, the development of this tone is disturbed in so far that its embouchure is less sure and delicate than on my flutes with open G sharp key. The difference can be seen at once in staccato pianissimo and in slurring deep tones with E3, for example G sharp2 and A2 with E3.

2. The ease in playing

The playing is made more difficult by the combination of keys described above for two reasons. As the key, which has to close the G sharp key airtight, needs a strong spring, the consequence is that in comparison with the open G sharp key, the third finger of the left hand needs more than the double force in order to overcome not only the spring of the A key but also the strong key of the G sharp key. Therefore, playing is not only made more difficult, but also beautiful trills on G sharp with A, A flat with B and D sharp 3 with E 3 become nearly impossible without great muscular strength and much practice.

Besides, the little finger of the left hand has always to do movements which are contrary to those of the fingers of the right hand, whenever G sharp or A flat changes with notes which are played with the finger of the right hand; nobody will deny that the same movements made simultaneously by the fingers of both hands are easier to be made than contrary movements, and that consequently the playing is made more difficult by the closed G sharp key.

It may be objected here that the G sharp or A flat and consequently also the little finger of the left hand are not used at all in several keys. This is true, indeed! – But as a good flute player has to be able today to play in all keys well and correctly, and as the G sharp or A flat is used in 16 keys among 24, the little finger of the left hand has to be trained as well as all the others.

3. Simplicity of the key mechanism

The difficulty to keep the key mechanism in order is increased by frequent use according to its complexity. The two combinations in my key system, that is the key combination with F sharp and B flat, are therefore only justified by the impossibility to close 11 holes with 9 fingers. But as the little finger of the left hand is only designated for the treatment of the G sharp key, there was no necessity, to make a third complicated key combination, which is in every respect only detrimental with regard to acoustics, ease in playing and simplicity of key mechanism. Even the objection “that the study of the new flute is made easier by the closed G sharp key for players of the old flute” is based only on deception, because a thorough study of the new flute cannot be made without long continued slow practice. And the experience with my pupils, who changed without prejudice from the old to the new flute, has proved often enough that the treatment of the open G sharp key with all the others is not only learned simultaneously but also quite imperceptibly. Even for older flute players some weeks of diligent practice are enough to regain the former execution in playing and several excellent artists, who changed from closed to open G sharp key on my advice, soon were convinced by the many and great advantages of the latter and thanked me for that. The fact that there are in Paris and other places great artists on flutes with closed G sharp key only proves that difficulties can be overcome by talent and diligence; this alone doesn’t prove that these artists would not have achieved an even greater execution with less trouble with the open G sharp key.

Before I conceived my key system, I had myself examined, tried and thoroughly thought over all parts of the key mechanism for a long period, because it was my intention to choose the best everywhere. And there-fore, I would still today observe every rational critic of my system with pleasure and I would gladly execute suggestions of real improvements.

3) Remarks

Theobald Böhm quotes in his letter two reasons, why he didn’t take position against the closed G sharp key earlier. First, he highly esteemed Louis Dorus, successor of Jean Louis Tulou at the Paris Conservatory, who adopted the Böhm flute already in 1837 as one of the first and who in 1838 changed from open to closed G sharp by the aid of Louis Lot (Welch, Christopher: History of the Boehm Flute. London 3rd ed. 1896, p. 58). Theobald Böhm dedicated him his opus 24 in 1845, the French translation of his book “On the Construction of Flutes and the latest Improvements” in 1848, and his opus 35 in 1857, and in his letter to his pupil Sebastian Ott from 3rd February 1869, he called him the first flautist of the world (In: Library of Congress, Washington, Miller Collection).

Secondly, he didn’t consider it necessary to comment publicly on the closed G sharp key, because with the exception of France, almost everywhere people played open G sharp. This was also true for America. On 29th November 1854, Böhm’s silver flute no. 85 was sent to the flautist Philipp Ernst in New York (Böhm, Theobald: Workshop Ledger. Munich 1847–1859, 1876–1879. In: Library of Congress, Washington, Miller Collection), and in 1864, Martin Heindl (Boston Symphony Orchestra) came to America and achieved great triumphs with Böhm’s silver flute no. 19. Theobald Böhm writes in his letter from ? May 1870 to his friend Walter S. Broadwood: “Since my former pupil Heindl travelled through the United States, I have had more orders than I can fulfill from America; and though I offered to procure flutes from my friend Lot, at Paris, people prefer to wait for those made by myself.” (In: Böhm, Theobald: On the Construction of Flutes and the latest Improvements. Munich 1847, ed. Walter S. Broadwood, London 1882, p. 58).

Nearly all flutes from the workshop of Theobald Böhm (1828–1839), Böhm & Greve (1839–1846), Theobald Böhm (1847–1861) and Böhm & Mendler (1862–1888) have open G sharp key. Only in very few cases, if expressively desired by the customer, Theobald Böhm made a closed G sharp key, reluctantly and against his conviction. According to his workshop ledger, from 1847–1859, he made 128 flutes with open and only 2 flutes (no. 3 and 22) with closed G sharp. Nearly all later flutes have open G sharp, too.

Today, most flautists play closed G sharp key with the exception of the Russia (Solum, John: Notes on a Recital Tour to the Soviet Union. In: Newsletter of the National Flute Association, New York January 1984, p. 24–25; Wye, Trevor: The Flute, the Hammer and the Sickle. In: Pan, London March 1985, p. 19), but there is a number of eminent flute players who play the Böhm flute in its original form with open G sharp key such as for example William Bennett, London and Denis Bouriakov, New York.

Literature

Boehm, Th. / Miller, D. C., The Flute and Flute Playing, 1922, p. 71

Böhm, Ludwig: Theobald Böhms Stellungnahme zur geschlossenen Gis-Klappe

In:

Japan Flutists Association, Tokyo 20. 2. 1984, S. 17–19

Das Musikinstrument, Frankfurt am Main April 1984, S. 54–57

Fomrhi Quarterly, Oxford April 1984, S. 44–47

The Washington Flute Scene, Washington Juni/Juli 1984, S. 3–6

Glareana, Zürich Juli 1984, S. 16–19

Tibia, Celle Oktober 1984, S. 206–209

The Flutist Quarterly, New York November 1984, S. 8 f.

Flöte aktuell, Frankfurt am Main Februar 1987, S. 22 (gekürzt)

Newsletter of the Australian Flute Association, Sydney Februar 1987, S. 5 f.; Mai 1987, S. 6 f.; August 1987, S. 6 f.

South Australian Flute News, Adelaide Februar 1987, S. 22–25

The Flute, Sydney November 1987, S. 12–14

Pan, London Dezember 1987, S. 19–22

Huilisti, Tampere Dezember 1989, S. 14–19

Journal Traversières, Lyon März 1990, S. 16–19

New Zealand Flute Society News, Christchurch September 1990, S. 29–34

Böhm, Ludwig: Festschrift zum 200. Geburtstag von Theobald Böhm. München 1994, S. 38–40

South Australian Flute News, Adelaide Juli 1994, S. 20–22

The Flute, Sydney November 1994, S. 42–44

Traversières Magazine, Paris Januar 2007, S. 58–60

Fluit, Amsterdam Januar 2007, S. 31–37

Japan Flutists Association, Tokyo Juni 2011, S. 37–41

Cooper, Albert: Gadget Page [Open or closed G sharp flute?]. In: Pan, Dezember 1983, S. 6

Giannini, Tula: An Old Key for a New Flute. The Boehm Flute with closed G sharp: Historical Perspectives. In: The Flutist Quarterly, New York October 1984, p. 15–20

Hünteler, Konrad: Die geschlossene Gis-Klappe. In: Busch-Salmen, G. / Krause-Pichler, A.: Handbuch Querflöte. Instrument, Lehrwerke, Aufführungspraxis, Musik, Ausbildung, Beruf. Kassel 1999, p. 40–41

Lawrence, Eleanor: Re-evaluating the G sharp Key: An Introduction. In: The Flutist Quarterly, New York October 1984, p. 6–7, 10–12

Lawrence, E. / Schultz, P.: Facts and Figures on Open G sharp Flutes. In: The Flutist Quarterly, New York Oktober 1984, p. 23.

Minzloff, Oliver: In Commemoration of Theobald Boehm’s 190th Anniversary, April 9, 1794. Open G sharp? Gee Whiz! In: The Flutist Quarterly, New York October 1984, p. 21–22. Flöte aktuell, Frankfurt am Main February 1987, p. 19–22

Pailthorpe, Daniel: Why I play Open G sharp. In: Pan, London December 1997, p. 14–16

Sachs, Gerhard: Offenes gis – geschlossenes gis auf der Böhmflöte. Akustische Betrachtungen. In: Flöte aktuell, Frankfurt am Main February 1987, p. 19

Ventzke, Karl: Die Gis-Klappe bei der Boehmflöte. In: Instrumentenbau-Zeitschrift, Siegburg April 1960, p. 205–206

Vogt, Linda: Bygone Flute Systems and the Flutists who played them in Australia. In: Flute Australia, Sydney May 1996, p. 6–8

Wimberly, David: Letter to the Editor. In: The Flutist Quarterly, New York March 1985, p. 3.

Wimberly, David: Alexander Murray: Vision Quest. In: The Flutist Quarterly, New York June 1985, p. 48–51

The flautist Konrad Hünteler describes his change from the open to the closed G sharp key and he rejects the closed G sharp key decidedly.

According to Lawrence/Schultz, numerous flute makers such as for example Lamberson, Powell and Selmer, recognize the superiority of the open G sharp key, but they only make few flutes with open G sharp because of the small demand.

Dayton C. Miller writes in his commentary that after careful examination of all different forms of the G sharp key, he changed to the open G sharp key and he recommends to all beginners to start with it.

The flautist Oliver Minzloff, who lives in Basel, who also changed to the open G sharp key, reports of a test with eight flute beginners. The four, who began with the open G sharp key could already play well after six months, whereas the four, who began with the closed G sharp key, were still having difficulties even after one and a half years with the contrary movement of the G sharp finger. As further disadvantages of the closed G sharp key, he mentions that out of 40 tones, the little finger is only moved 5 times and therefore remains untrained (with open G sharp key, it is moved 22 times), that the E 3 becomes too high and that the E-mechanism causes new problems.

The flute maker Gerhard Sachs particularly indicates the acoustical disadvantages of the closed G sharp key. Besides the detrimental E-mechanism, the chimney of the additional tone hole widens the tube and makes the tone deeper. By the additional G sharp hole, the D 3 frequently becomes too high and the colour of the tone of the closed G sharp is different from the tones B, A or G.

David Wimberly reports in his letter to the editor that Jack Moore and he made about 80 flutes with open G sharp key, that they had sold them mostly in the United States and that numerous flautists had confirmed him that after a time of about three months of learning the new system, they experienced the open G sharp key as clearly more comfortable and more logical than the closed G sharp key. According to David Wimberly, the closed G sharp key is inferior acoustically to the open G sharp key in all three octaves. The pads and fastenings are less durable. Wimberly describes in his article the new model of the so-called “Murray flute”, which was made by him and Jack Moore in 1985, and which has, besides an open G sharp key and some more peculiarities also an open D sharp key.

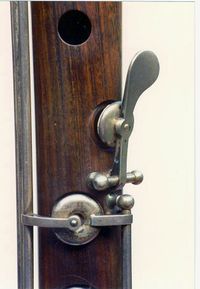

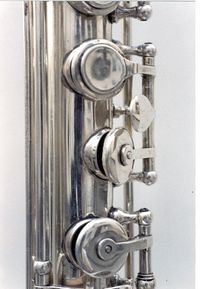

The photos are from my “Verzeichnis der erhaltenen Flöten von Theobald Böhm“ / Catalogue of the still existing Flutes of Theobald Böhm“.

1 Closed G sharp key, conical flute of old construction of Theobald Böhm (Munich, Deutsches Museum 2009-150)

2 Open G sharp key, conical ring-keyed flute of Theobald Böhm (Frankfurt am Main, private collection 83125)

3 Open G sharp key, cylindrical flute no. 30 of Theobald Böhm (Munich, Deutsches Museum 2009-156)

4 Open G sharp key, cylindrical flute of Theobald Böhm, 1854 system (Frankfurt am Main, private collection 85068)

5 Open G sharp key, cylindrical flute of Böhm & Mendler, thinned wood with raised tone hole chimneys (Washington, Library of Congress, Miller 306)

6 Closed G sharp key, cylindrical flute of Böhm & Mendler, modified Dorus G sharp key without additional tone hole. The G sharp key is open in repose (Frankfurt am Main, private collection 86590)

7 Closed G sharp key, cylindrical flute of Böhm & Mendler, Böhm G sharp key without additional tone hole. The G sharp key is closed in repose. Macauley flute with gold plates (Washington, Library of Congress, Miller 161)

8 Closed G sharp key, cylindrical flute of Böhm & Mendler, with additional tone hole on the reverse side (Stuttgart, private collection)

L’opinion de Theobald Böhm sur la clé sol dièse ouverte

par Ludwig Böhm (2014)

En 1981, cinq lettres de Theobald Böhm à Wilhelm Popp ont apparu en Suède grâce à mon annonce de recherche dans un journal de musique, qui se trouvent aujourd’hui aux Archives municipales (Stadtarchiv) de Munich, héritage Theobald Böhm I. Dans sa lettre du 5 février 1865, Theobald Böhm s’est occupé en détail de la clé de sol dièse ouverte et fermée. Le papier ajouté à cette lettre contient la version abrégée de l’article de Theobald Böhm sur la clé de sol dièse ouverte. Peu après, il a écrit aussi une version un peu plus détaillée, qui est conservée comme brouillon (Bayerische Staatsbibliothek / Bibliothèque national bavaroise, Munich) ou comme copie en net (Library of Congress, Washington), et qu’il a traduite lui-même en anglais (Bayerische Staatsbibliothek, Munich) et en français (Stadtarchiv Munich). Rien n’a été publié, mais le thème a été traité encore une fois dans son livre “Die Flöte und das Flötenspiel in akustischer, technischer und artistischer Beziehung / La flûte et le jeu de la flûte en son aspect acoustique, technique et artistique”, Munich 1871, p. 20–22.

1) Lettre de Theobald Böhm à Wilhelm Popp

Munich, le 5 février 1865

Cher Monsieur,

Vous aviez raison de recommander une flûte de moi au lieu de Lot à Paris, parce que mon système de clés entièrement logique a été seulement rendu pire en ses aspects acoustique et mécanique par le premier flûtiste Dorus à Paris, qui a fait une amélioration prétendue par une clé de sol dièse fermée. Après mûre réflexion, j’ai fait une simple clé de sol dièse ouverte, parce que toutes les clés de ma flûte de mi 1 jusqu’à l’aigu correspondent au mouvement naturel des doigts, quand elles sont fermées ou ouvertes par les doigts. Dorus pensait rendre la flûte plus accessible aux joueurs de l’ancienne flûte en faisant une clé de sol dièse fermée, à laquelle ils étaient accoutumés, mais il ne considérait pas qu’il a obtenu ainsi plus de désavantages que des avantages.

Lot a fait cela pour lui, en unissant la clé de sol dièse ouverte avec la clé de la. Ainsi, on obtient sol dièse en baissant l’annulaire de la main gauche comme dans l’ancienne flûte et pour obtenir sol dièse, on doit lever la clé de sol dièse avec le petit doigt, comme sur l’ancienne flûte. Cependant, la conséquence est que les deux tons, sol et sol dièse sont produits comme sur l’ancienne flûte, tandis que dans mon système, le sol est fait en fermant la clé de sol dièse avec le petit doigt el le sol dièse est fait en levant ce doigt. J’ai fait cela après une longue considération et toute personne qui réfléchit à l’affaire doit être d’accord avec moi.

Dorus lui même devait confesser qu’il avait fait une folie, quand je lui ai expliqué l’affaire et moi aussi j’ai fait une folie pour l’amour de Dorus, parce que je n’ai pas expliqué immédiatement à cette époque l’impropriété de la clé de sol dièse fermée. Comme Dorus était déjà premier flûtiste à Paris, naturellement tous ses élèves ont adopté la flûte comme il la jouait. Mais beaucoup se sont accoutumés plus tard à la clé de sol dièse ouvert et même de Vroye m’a dit, quand je lui ai expliqué l’affaire l’année dernière, qu’il regrettait de ne pas être capable de faire un autre changement, parce que naturellement il aurait dû étudier en profondeur encore une fois pour quelque temps. Mais comme de Vroye essaie maintenant, sans doute, de vendre des flûtes avec la clé de sol dièse fermée en Allemagne parce qu’il reçoit plus de commission de Lot que de moi, je vais expliquer l’affaire très probablement en public dans le futur proche. Jusqu’à présent, je n’ai pas considéré que cela valait la peine, parce qu’en Allemagne, en Angleterre, en Russie et presque partout avec l’exception de la France, tous les flûtistes jouent seulement d’après mon système. Dans le papier joint, vous trouverez une explication des avantages et des désavantages et vous accepterez sans doute la justesse de mes explications.

Votre devoué

Th. Boehm

2) Article de Theobald Böhm (version de Washington) : Observations sur les changements apportés à Paris au système de clés de la dite “Flûte Boehm”

Les nécessités d’une bonne flûte sont d’abord la perfection acoustique de ton et d’accord, la facilité de jeu et la simplicité du mécanisme des clés. Si et comment ces nécessités s’acquièrent mieux par une clé de sol dièse ouverte ou fermée est une question qui intéresse certainement tous ceux qui jouent ou veulent jouer la flûte Boehm.

1. L’acoustique de l’instrument

À moyen de la combinaison d’une clé de sol dièse fermée avec la clé de la ouverte, le neuvième trou ou trou de la ne peut jamais être ouvert seul et parce que le huitième trou ou trou de sol dièse est situé trop loin bas dans la flûte pour pouvoir servir pour le haut mi 3 comme trou de ton, la formation de ce ton est dérangé de manière que son embouchure est moins sûre et délicate que dans mes flûtes avec sol dièse ouvert. La différence peut être perçue immédiatement en jouant staccato pianissimo et en liant des tons bas avec mi 3, par exemple sol dièse 2 et la 2 avec mi 3.

2. La légèreté de jeu

Jouer devient plus difficile par la combinaison des clés décrites au-dessus par deux raisons. Comme la clé que doit fermer hermétiquement la clé de sol dièse nécessite un ressort fort, en comparaison avec la clé sol dièse ouvert, le troisième doigt de la main gauche nécessite plus que la double force pour vaincre non seulement le ressort de la clé de la, mais aussi le fort ressort de la clé sol dièse. C’est pourquoi non seulement jouer est rendu plus difficile, mais aussi de bons trilles sur sol dièse avec la, lab avec si bémol et ré dièse 3 avec mi 3 deviennent presque impossible sans une grande force musculaire et beaucoup de pratique.

En outre, le petit doigt de la main gauche doit toujours effectuer des mouvements contraires à ceux des doigts de la main droite, et toujours quand sol dièse ou lab change avec des notes jouées avec les doigts de la main droite; personne ne va nier que les mêmes mouvements effectués simultanément par les doigts des deux mains sont plus faciles à faire que des mouvements contraires et par conséquent, jouer devient plus difficile avec la clé de sol dièse fermée.

On peut objecter ici que le sol ou lab, et par conséquent aussi le petit doigt de la main gauche, ne sont pas utilisés du tout dans plusieurs tons. C’est vrai, en effet. Mais comme un bon flûtiste doit être capable aujourd’hui de jouer bien et correctement dans tous les tons, et comme le sol dièse ou lab est utilisé dans 16 tons entre 24, le petit doigt de la main gauche doit être entraîné comme tous les autres.

3. Simplicité du mécanisme des clés

La difficulté de maintenir le mécanisme des clés en ordre est augmenté par la complexité de son emploi fréquent. Les deux combinaisons de mon système de clé, c’est-à-dire la combinaison des clés avec fa dièse et si bémol, sont justifiées seulement par l’impossibilité de fermer 11 trous avec neuf doigts. Mais comme le petit doigt de la main gauche est destiné seulement au traitement de la clé de sol dièse, il n’existait pas une nécessité de faire une troisième combinaison de clés compliquée, à tous égards nuisible au respect de l’acoustique, de la légèreté de jouer et de la simplicité du mécanisme des clés. Même l’objection “que l’étude de la nouvelle flûte est rendu plus facile par la clé sol dièse fermé pour joueurs de la vielle flûte” repose seulement sur une illusion, parce qu’une étude profonde de la nouvelle flûte ne peut pas être fait sans des exercices lents nécessitant beaucoup de temps. Et l’expérience faite auprès de mes élèves, qui ont échangé sans préjudices la vieille flûte contre la nouvelle, a prouvé maintes fois que l’utilisation de la clé de sol dièse et de toutes les autres non seulement est apprise simultanément, mais aussi assez imperceptiblement. Même pour des joueurs plus âgés, quelques semaines de pratique diligente suffisent pour récupérer l’habilité antérieure de jouer et beaucoup d’artistes excellents, qui sont passés de la clé de sol dièse fermée à la clé ouverte en suivant mon conseil, ont été bientôt convaincu des nombreux et grands avantages de cette dernière et m’ont remercié pour cela. Le fait qu’il se trouve à Paris et dans d’autres lieux de grands artistes jouant une flûte avec la clé de sol de dièse fermée, seulement prouve que des difficultés peuvent être vaincues par talent et diligence; cela seul ne prouve pas que ces artistes n’auraient pas obtenu une exécution encore plus grande avec moins de peine grâce à la clé de sol dièse ouverte.

Avant de concevoir mon système de clés, j’avais examiné, m’étais exercé et avais réfléchi à toutes les parties du mécanisme des clés pendant longtemps, parce qu’il était de mon intention de choisir le meilleur dans toutes les parties. C’est pourquoi je vais observer encore aujourd’hui chaque critique rationnelle de mon système avec plaisir et je vais exécuter volontiers des propositions d’améliorations réelles.

3) Annotations

Theobald Böhm a cité dans sa lettre deux raisons pour lesquelles il n’a pas pris position contre la clé de sol dièse fermée plus tôt. Premièrement, il appréciait beaucoup Louis Dorus, successeur de Jean Louis Tulou dans le Conservatoire de Paris, qui avait été parmi les premiers à adopter la flûte Böhm dès 1837 et qui a changé en 1838 la clé de sol dièse ouverte en clé à fermée avec l’aide de Louis Lot (Welch, Christopher: History of the Boehm Flute. Londres 3e edition 1896, p. 58). Theobald Böhm lui a dedié son opus 24 en 1845, la traduction française de son livre “Über den Flötenbau und die neuesten Verbesserungen desselben / De la fabrication de la flûte et de ses derniers améliorations“ en 1848 et son opus 35 en 1857. Dans sa lettre à son élève Sebastian Ott du 3 février 1869, il l’a appelé le meilleur flûtiste du monde (dans: Library of Congress, Washington, collection Miller).

Deuxièmement, il ne considérait pas comme nécessaire de commenter en public la clé de sol dièse fermée, parce qu’à l’exception de la France, presque partout les gens jouaient avec le sol dièse ouvert. C’est juste aussi pour les Ètats-Unis. Le 29 novembre 1854, la flûte en argent no. 85 de Böhm a été envoyée au flûtiste Philipp Ernst à New York (Böhm, Theobald: Geschäftsbuch der Flötenwerkstatt / Livre de l’atelier. Munich 1847–1859, 1876–1879, dans: Library of Congress, Washington, collection Miller), en 1864, Martin Heindl (Boston Symphony Orchestra) est arrivé en Amérique et il a obtenu de grands triomphes avec la flûte de Böhm en argent no. 19. Theobald Böhm écrit dans sa lettre de mai 1870 à son ami Walter S. Broadwood: “Depuis que mon ancien élève a voyagé à travers les États-Unis, j’ai eu plus de commandes d’Amérique que je n’en peux exécuter; et quoique j’aie offert de procurer des flûtes de mon ami Lot à Paris, les gens préfèrent attendre celles qui sont fabriquées par moi.” (dans: On the Construction of Flutes and the latest Improvements. Munich 1847, ed. Walter S. Broadwood, London 1882, p. 58).

Presque toutes les flûtes de l’atelier de Theobald Böhm (1828–1839), Böhm & Greve (1839–1846), Theo-bald Böhm (1847–1861) et Böhm & Mendler (1862–1888) possèdent une clé de sol dièse ouvert. Seulement dans très peu de cas, lorsque c’était expressément desiré par le client, Theobald Böhm faisait une clé de sol dièse fermée, avec répugnance et contre sa conviction. D’après son livre d’atelier, de 1847 à 1859, il a fabriqué 128 flûtes avec clé de sol dièse ouvert et seulement deux flûtes (no. 3 et 22) avec sol dièse fermé. Presque toutes les flûtes postérieures ont aussi un sol dièse ouvert.

Aujourd’hui, la majorité des flûtistes joue la clé de sol dièse fermée avec l’exception de la Russie (Solum, John: Notes on a Recital Tour to the Soviet Union. Dans: Newsletter of the National Flute Association, Nouvelle York janvier 1984, p. 24–25; Wye, Trevor: The Flute, the Hammer and the Sickle. Dans: Pan, Londres mars 1985, p. 19), mais il y a aussi un nombre de flûtistes éminents qui jouent la flûte Böhm dans sa forme originale avec la clé de sol dièse ouvert, par exemple William Bennett, à Londres et Denis Bouriakov, à New York.

Literature

Boehm, Th. / Miller, D. C., The Flute and Flute Playing, 1922, p. 71

Böhm, Ludwig: Theobald Böhms Stellungnahme zur geschlossenen Gis-Klappe

Dans:

Japan Flutists Association, Tokyo 20. 2. 1984, S. 17–19

Das Musikinstrument, Frankfurt am Main April 1984, S. 54–57

Fomrhi Quarterly, Oxford April 1984, S. 44–47

The Washington Flute Scene, Washington Juni/Juli 1984, S. 3–6

Glareana, Zürich Juli 1984, S. 16–19

Tibia, Celle Oktober 1984, S. 206–209

The Flutist Quarterly, New York November 1984, S. 8 f.

Flöte aktuell, Frankfurt am Main Februar 1987, S. 22 (gekürzt)

Newsletter of the Australian Flute Association, Sydney Februar 1987, S. 5 f.; Mai 1987, S. 6 f.; August 1987, S. 6 f.

South Australian Flute News, Adelaide Februar 1987, S. 22–25

The Flute, Sydney November 1987, S. 12–14

Pan, London Dezember 1987, S. 19–22

Huilisti, Tampere Dezember 1989, S. 14–19

Journal Traversières, Lyon März 1990, S. 16–19

New Zealand Flute Society News, Christchurch September 1990, S. 29–34

Böhm, Ludwig: Festschrift zum 200. Geburtstag von Theobald Böhm. München 1994, S. 38–40

South Australian Flute News, Adelaide Juli 1994, S. 20–22

The Flute, Sydney November 1994, S. 42–44

Traversières Magazine, Paris Januar 2007, S. 58–60

Fluit, Amsterdam Januar 2007, S. 31–37

Japan Flutists Association, Tokyo Juni 2011, S. 37–41

Cooper, Albert: Gadget Page [Open or closed G sharp flute?]. In: Pan, Dezember 1983, S. 6

Giannini, Tula: An Old Key for a New Flute. The Boehm Flute with closed G sharp: Historical Perspectives. Dans: The Flutist Quarterly, New York octobre 1984, p. 15–20

Hünteler, Konrad: Die geschlossene Gis-Klappe. Dans: Busch-Salmen, G. / Krause-Pichler, A.: Handbuch Querflöte. Instrument, Lehrwerke, Aufführungspraxis, Musik, Ausbildung, Beruf. Kassel 1999, p. 40–41

Lawrence, Eleanor: Re-evaluating the G sharp Key: An Introduction. Dans: The Flutist Quarterly, New York octobre 1984, S. 6–7, 10–12

Lawrence, E. / Schultz, P.: Facts and Figures on Open G sharp Flutes. Dans: The Flutist Quarterly, New York octobre 1984, p. 23.

Minzloff, Oliver: In Commemoration of Theobald Boehm’s 190th Anniversary, April 9, 1794. Open G sharp? Gee Whiz! Dans: The Flutist Quarterly, New York octobre 1984, p. 21–22. Flöte aktuell, Frankfurt am Main février 1987, p. 19–22

Pailthorpe, Daniel: Why I play Open G sharp. Dans: Pan, London décembre 1997, p. 14–16

Sachs, Gerhard: Offenes gis – geschlossenes gis auf der Böhmflöte. Akustische Betrachtungen. Dans: Flöte aktuell, Frankfurt am Main février 1987, p. 19

Ventzke, Karl: Die Gis-Klappe bei der Boehmflöte. Dans: Instrumentenbau-Zeitschrift, Siegburg avril 1960, p. 205–206

Vogt, Linda: Bygone Flute Systems and the Flutists who played them in Australia. Dans: Flute Australia, Sydney mai 1996, p. 6–8

Wimberly, David: Letter to the Editor. Dans: The Flutist Quarterly, New York mars 1985, p. 3.

Wimberly, David: Alexander Murray: Vision Quest. Dans: The Flutist Quarterly, New York juin 1985, p. 48–51

Le flûtiste Konrad Hünteler décrit son passage de la clé de sol dièse fermée à la clé de sol dièse ouverte et il rejette la clé sol dièse fermée fermement.

D‘après Lawrence/Schultz, de nombreux facteurs de flûte, comme par exemple Lamberson, Powell et Selmer, reconnaissent la supériorité de la clé sol dièse ouvert, mais ils fabriquent seulement peu de flûtes à cause du peu de demande.

Dayton C. Miller écrit dans son commentaire que après d’examiner profondément toutes les formes de la clé sol dièse, il a changé à la clé sol dièse ouvert et il recommande à tous les débutants de commencer avec cela.

Le flûtiste Oliver Minzloff, qui vit à Bâle et qui est passé aussi à la clé de sol dièse ouvert, rapporte un essai avec huit débutants à la flûte. Les quatre, qui ont commençé avec la clé sol dièse ouvert, pouvaient jouer bien déjà après six mois, tandis que les quatre, qui ont commençé avec la clé sol dièse fermée aussi encore après un ans et demi avaient des problèmes avec le mouvement contraire du doigt pour le sol dièse. Comme d’autres désavantages de la clé de sol dièse fermée, il mentionne que le petit doigt est mû seulement dans 5 notes sur 40 et c’est pourquoi il reste non entraîné (chez la clé sol dièse ouverte 22 fois), tandis que le mi3 devient trop haut et que la mécanique cause de nouveaux problèmes.

Le facteur de flûtes Gerhard Sachs indique surtout les désavantages acoustiques de la clé de sol dièse fermée. À côté de la mécanique du mi désavantageuse, la cheminée du trou de ton supplémentaire élargit le tube et rend le ton plus bas. Avec le trou de sol dièse additionnel, le mi dièse3 devient frequemment trop haut et la couleur de la note sol dièse avec clé fermée est autre que celle des notes si bémol, la ou sol.

David Wimberly rapporte dans sa lettre a l’éditeur que Jack Moore et lui avaient fabriqué environ 80 flûtes avec clé de sol dièse ouverte, vendues le plus souvent dans les Etats-Unis, et que de nombreux flûtistes avaient confirmé que après un temps d’étudier autrement d’environ trois mois, ils trouvaient la clé sol dièse ouverte beaucoup plus commode et plus logique que la clé sol dièse fermé. D‘après David Wimberly, la clé de sol dièse ouverte est inférieure acoustiquement à la clé sol dièse ouverte dans l’ensemble des trois octaves. Les tampons et les fixations sont moins solides. Wimberly décrit dans son article le nouveau modèle dit „flûte Murray“, fait en 1985 par lui et Jack Moore, qu’il possède, à côté d‘une clé sol dièse ouverte et quelques autres particularités comme une clé de ré dièse ouverte.

Les photos proviennent de mon “Verzeichnis der erhaltenen Flöten von Theobald Böhm“ / Catalogue des flûtes conservées de Theobald Böhm“

1 Clé sol dièse fermée, flûte conique d’ancien construction de Theobald Böhm, (Munich, Deutsches Museum 2009-150)

2 Clé sol dièse ouvert, flûte conique d’anneaux (Frankfurt am Main, collection privèe 83125)

3 Clé sol dièse ouvert, flûte cylindrique no. 30 de Theobald Böhm (Munich, Deutsches Museum 2009-156)

4 Clé sol dièse ouvert, flûte cylindrique de Theobald Böhm, système 1854 (Frankfurt am Main, collection privèe 85068)

5 Clé sol dièse ouvert, flûte cylindrique de Böhm & Mendler, bois amincé avec des cheminés des trous de ton élevés (Washington, Library of Congress Miller 306)

6 Clé sol dièse fermé, flûte cylindrique de Böhm & Mendler, clé Dorus sol dièse modifiée sans trou de ton additionnel. La clé sol dièse est ouvert en repos (Frankfurt am Main, collection privèe 86590)

7 Clé sol dièse fermé, flûte cylindrique de Böhm & Mendler, clé Böhm sol dièse sans trou de ton additionnel. La clé sol dièse est fermé en repos. Flûte de Macauley avec des plaquettes d’or (Washington, Library of Congress, Miller 161)

8 Clé sol dièse fermé, flûte cylindrique de Böhm & Mendler, avec un trou additionnel au revers (Stuttgart, collection privèe)

La opinión de Theobald Böhm sobre la llave de Sol sostenido abierta

por Ludwig Böhm (2014)

En 1981, cinco cartas de Theobald Böhm a Wilhelm Popp aparecieron en Suecia por medio de mi anuncio de búsqueda en una revista de música. Estas cartas se encuentran actualmente en el Stadtarchiv (Archivo Municipal) de Munich, herencia Theobald Böhm. En su carta del 5 de febrero de 1865, Theobald Böhm discutió extensamente sobre la llave de Sol sostenido abierta y cerrada. El papel adjunto a esta carta contiene la versión resumida del artículo de Theobald Böhm sobre la llave de Sol sostenido. Poco después escribió una versión un poco más amplia que todavía existe como borrador (Bayerische Staatsbibliothek / Biblioteca Nacional Bávaro, Munich) y como copia en limpio (Library of Congress, Washington) y que tradujo él mismo al inglés (Bayerische Staatsbibliothek, Munich) y al francés (Stadtarchiv Munich). Nada fue publicado, pero el asunto fue tratado una vez más en su libro “Die Flöte und das Flötenspiel in akustischer, technischer und artistischer Beziehung / La flauta y la ejecución en la flauta en aspecto acústico, técnico y artístico“, Múnich 1871, p. 20–22.

1) Carta de Theobald Böhm a Wilhelm Popp

Munich, 5 de febrero de 1865

Estimado señor,

Ud. tenía razón en recomendar una flauta hecha por mí en lugar de por Lot en París, porque mi sistema de llaves completamente lógico solamente fue empeorado en el aspecto acústico y mecánico por el primer flautista Dorus en París, quien hizo una pretendida mejora incorporando una llave de Sol sostenido cerrada. Después de una madura reflexión, hice una llave de Sol sostenido abierta simple, porque todas las llaves de mi flauta desde Mi 1 hacia arriba corresponden al movimiento natural de los dedos, cuando son cerradas y abiertas por los dedos. Dorus pensó hacer la nueva flauta más accesible para los intérpretes del modelo de flauta antigua haciendo una llave de Sol sostenido cerrada como estaban acostumbrados, pero no consideró que eso tendría más desventajas que ventajas.

Lot hizo esto para él uniendo la llave de Sol sostenido con la llave La. De este modo, se obtiene la nota Sol presionando hacia abajo con el dedo anular de la mano izquierda como en la flauta antigua, y para obtener Sol sostenido se tiene que presionar hacia arriba la llave de Sol sostenido con el dedo meñique, como en la flauta antigua. Sin embargo, la consecuencia fue que ambas notas, Sol y Sol sostenido son producidas como en la flauta antigua, mientras que con mi sistema, el Sol se hace cerrando la llave Sol sostenido con el dedo meñique y el Sol sostenido se obtiene levantando este dedo. Hice esto después de largas consideraciones y todo el mundo que reflexione sobre el asunto, estará de acuerdo conmigo.

El mismo Dorus, cuando yo le expliqué el asunto, tuvo que confesar que cometió un error estúpido y al mismo tiempo yo también cometí otro error estúpido por mi cariño hacia Dorus, al no explicar inmediatamente en ese momento lo inapropiado de la llave de Sol sostenido cerrada. Como Dorus era ya el primer flautista de París, naturalmente todos sus alumnos adoptaron la flauta tal y como él la tocaba. Pero muchos se acostumbrarían más tarde a la llave de Sol sostenido abierta, e incluso De Vroye me dijo, cuando le expliqué el asunto el año pasado, que sentía no haber sido capaz de haber hecho otro cambio, porque naturalmente ahora tendría que estudiar intensamente otra vez durante algún tiempo. Pero como De Vroye ahora sin duda intenta vender flautas con llave de Sol sostenido cerrada en Alemania, porque recibe más comisión de Lot que de mí, probablemente voy a tratar de explicar más el asunto en público en un futuro próximo. Hasta ahora, no había considerado que valiera la pena, porque en Alemania, Inglaterra, Rusia y casi en todas partes con la excepción de Francia, todos los flautistas solo tocan según mi sistema. En el papel adjunto, Ud. encontrará una explicación de las ventajas y desventajas y Ud. aceptará sin duda la rectitud de mis explicaciones.

Su seguro servidor

Th. Boehm

2) Artículo por Theobald Böhm (versión Washington): Observaciones sobre los cambios hechos en París en el sistema de llaves de la llamada “flauta Boehm”

Las necesidades de una buena flauta son, primero la perfección acústica y la afinación, la facilidad de tocar y la simplicidad del mecanismo de las llaves. Cómo y hasta qué punto estas necesidades pueden ser mejor suplidas por una llave de Sol sostenido abierta o cerrada es una pregunta que interesará seguramente a todos los que tocan o quieren aprender a tocar la flauta Boehm.

1. La acústica del instrumento

Por medio de la combinación de una llave de Sol sostenido cerrada con la llave de La abierta, el noveno agujero o agujero de La nunca puede ser abierto independientemente y como el octavo agujero o agujero de Sol sostenido está situado demasiado lejos hacia abajo en la flauta para poder servir como agujero de ventilación al Mi 3 agudo, la formación de este tono está turbada en tal medida, que su embocadura resulta menos segura y delicada que en mis flautas con llave de Sol sostenido abierto. La diferencia puede ser vista inmediatamente en staccato pianísimo y en el ligado de notas graves con Mi 3, por ejemplo Sol sostenido 2 y La 2 con Mi 3.

2. La agilidad de tocar

Tocar se hace más difícil por la combinación de llaves descrita arriba por dos razones. Como la llave que tiene que cerrar la llave de Sol sostenido herméticamente necesita un muelle fuerte, la consecuencia es que en comparación con la llave de Sol sostenido abierta, el tercer dedo de la mano izquierda necesita más del doble de fuerza para vencer no solo el muelle de la llave de La, sino también el fuerte muelle de la llave de Sol sostenido Por eso, no solo tocar resulta más difícil, sino que también trinos bonitos de Sol sostenido con La, Lab con Si y Re sostenido 3 con Mi 3 resultan casi imposibles sin emplear una gran fuerza muscular y mucho estudio.

Además, el dedo meñique de la mano izquierda siempre tiene que hacer movimientos contrarios a los de los dedos de la mano derecha como cuando Sol sostenido o Lab se alternan con notas tocadas con los dedos de la mano derecha; nadie puede negar que los mismos movimientos hechos simultáneamente por los dedos de ambos manos son más fácil de hacer que movimientos contrarios y que por consiguiente, tocar se hace más difícil por la llave de Sol sostenido cerrada.

Se puede objetar aquí que el Sol sostenido o el Lab, y por consiguiente también el dedo meñique de la mano izquierda no son utilizados en absoluto en varias tonalidades. Eso es verdad, ¡en efecto! – Pero como un buen flautista hoy día tiene que ser capaz de tocar bien y correctamente en todas las tonalidades y como el Sol sostenido o el Lab se utilizan en 16 tonalidades entre 24, el dedo meñique de la mano izquierda tiene que ser tan bien entrenado como todos los demás.

3. Simplicidad del mecanismo de llaves

La dificultad de mantener el mecanismo de llaves en perfecto estado por su uso frecuente se ve incrementada en relación a su complejidad. Las dos combinaciones en mi sistema de llaves, o sea la combinación de llaves de Fa sostenido y Si Bemol, está justificada solo por la imposibilidad de cerrar 11 agujeros con nueve dedos. Pero como el dedo meñique de la mano izquierda está solo designado para manejar la llave de Sol sostenido no había necesidad de hacer una tercera combinación complicada de llaves, que en todo caso solo es perjudicial en relación a la acústica, agilidad de tocar y simplicidad del mecanismo de llaves. Incluso la objeción de que “el estudio de la nueva flauta se hace más fácil por la llave de Sol sostenido cerrada para intérpretes de la antigua flauta” solamente está basada en el engaño, porque un estudio profundo de la flauta nueva no puede ser hecho sin un largo, continuado y lento entrenamiento. Y la experiencia con mis alumnos, que sin prejuicio cambiaron de la antigua a la nueva flauta, ha probado suficientemente que la manipulación de la llave de sol sostenido con todas las otras no solo se aprende simultáneamente, sino también de un modo casi imperceptible. Incluso para flautistas más mayores unas pocas semanas de práctica diligente son suficientes para recobrar la anterior habilidad de tocar, y muchos excelentes artistas que, siguiendo mi consejo cambiaron de la llave de Sol sostenido cerrada a la abierta, pronto se vieron convencidos por las muchas y grandes ventajas de la segunda, y por ello me lo agradecieron. El hecho de que en París y otros lugares haya grandes artistas que tocan la flauta con llave de Sol sostenido cerrada solo prueba que las dificultades pueden ser superadas con talento y diligencia; esto solo no prueba que estos artistas no hubieran alcanzado una ejecución incluso mayor y con menos problemas utilizando la llave de Sol sostenido abierta.

Antes de concebir mi sistema de llaves, examiné, probé y reflexioné profundamente sobre todas las partes del mecanismo de llaves durante largo tiempo, porque era mi intención elegir el mejor entre todos. Y por eso, todavía hoy contemplaría con placer cualquier crítica racional que se hiciera de mi sistema y ejecutaría gustosamente proposiciones de mejoras reales.

3) Anotaciones

Theobald Böhm cita en su carta dos razones, por las cuales no se posicionó antes contra la llave de Sol sostenido cerrada. Primero, apreciaba mucho a Louis Dorus, sucesor de Jean Louis Tulou en el Conservatorio de París, el cual adoptó la flauta Böhm ya en 1837 como uno de los primeros intérpretes y que cambió en 1838 la llave de Sol sostenido abierta a cerrada con la ayuda de Louis Lot (Welch, Christopher: History of the Boehm Flute. London 3° edición 1896, p. 58). Theobald Böhm le dedicó su opus 24 en 1845, la traducción francesa de su libro “Über den Flötenbau und die neuesten Verbesserungen desselben / De la construcción de la flauta y sus últimas mejoras “en 1848 y su opus 35 en 1857. En su carta a su alumno Sebastian Ott del 3 de febrero de 1869, lo calificó como el primer flautista del mundo (en: Library of Congress, Washington, colección Miller).

En segundo lugar, no consideró necesario comentar públicamente la llave de Sol# cerrada porque, con la excepción de Francia, casi en todas partes la gente tocaba con Sol sostenido abierta. Esto también era válido para los Estados Unidos. El 29 de noviembre de 1854, la flauta Böhm de plata no. 85 fue enviada al flautista Philipp Ernst en Nueva York (Böhm, Theobald: Geschäftsbuch der Flötenwerkstatt / Libro del taller. Munich 1847–1859, 1876–1879, en: Library of Congress, Washington, colección Miller), y en 1864, Martin Heindl (Boston Symphony Orchestra) llegó a América y obtuvo grandes triunfos con la flauta de Böhm en plata no. 19. Theobald Böhm escribe en su carta de mayo de 1870 a su amigo Walter S. Broadwood: “Desde que mi anterior alumno Heindl viajó por los Estados Unidos, tuve más encargos de América de los que puedo ejecutar; y aunque les ofrezco conseguir flautas de mi amigo Lot de París, la gente prefiere esperar a las flautas que están fabricadas por mí mismo.” (en: On the Construction of Flutes and the latest Improvements. Munich 1847, ed. Walter S. Broadwood, London 1882, p. 58).

Casi todas las flautas del taller de Theobald Böhm (1828–1839), Böhm & Greve (1839–1846), Theobald Böhm (1847–1861) y Böhm & Mendler (1862–1888) tienen la llave de Sol sostenido abierta. Solo en muy pocos casos, si era expresamente deseado por el cliente, Theobald Böhm construyó una llave de Sol sostenido cerrada, de mala gana y en contra de su convicción. Según su libro del taller, de 1847 a 1859 hizo 128 flautas con llave de Sol sostenido abierta y solo dos flautas (no. 3 y 22) con de Sol sostenido cerrada. Casi todas las flautas posteriores tienen también la de Sol sostenido abierta.

Hoy, la mayoría de los flautistas tocan con llave de Sol sostenido cerrada con la excepción de Rusia (Solum, John: Notes on a Recital Tour to the Soviet Union. En: Newsletter of the National Flute Association, Nueva York enero 1984, p. 24–25; Wye, Trevor: The Flute, the Hammer and the Sickle. En: Pan, Londres marzo 1985, p. 19), pero existe un número de eminentes flautistas que tocan la flauta Böhm en su forma original con la llave de Sol sostenido abierta, como por ejemplo William Bennett en Londres y Denis Bouriakov en Nueva York.

Bibliografía

Boehm, Th. / Miller, D. C., The Flute and Flute Playing, 1922, p. 71

Böhm, Ludwig: Theobald Böhms Stellungnahme zur geschlossenen Gis-Klappe

En:

Japan Flutists Association, Tokyo 20. 2. 1984, S. 17–19

Das Musikinstrument, Frankfurt am Main April 1984, S. 54–57

Fomrhi Quarterly, Oxford April 1984, S. 44–47

The Washington Flute Scene, Washington Juni/Juli 1984, S. 3–6

Glareana, Zürich Juli 1984, S. 16–19

Tibia, Celle Oktober 1984, S. 206–209

The Flutist Quarterly, New York November 1984, S. 8 f.

Flöte aktuell, Frankfurt am Main Februar 1987, S. 22 (gekürzt)

Newsletter of the Australian Flute Association, Sydney Februar 1987, S. 5 f.; Mai 1987, S. 6 f.; August 1987, S. 6 f.

South Australian Flute News, Adelaide Februar 1987, S. 22–25

The Flute, Sydney November 1987, S. 12–14

Pan, London Dezember 1987, S. 19–22

Huilisti, Tampere Dezember 1989, S. 14–19

Journal Traversières, Lyon März 1990, S. 16–19

New Zealand Flute Society News, Christchurch September 1990, S. 29–34

Böhm, Ludwig: Festschrift zum 200. Geburtstag von Theobald Böhm. München 1994, S. 38–40

South Australian Flute News, Adelaide Juli 1994, S. 20–22

The Flute, Sydney November 1994, S. 42–44

Traversières Magazine, Paris Januar 2007, S. 58–60

Fluit, Amsterdam Januar 2007, S. 31–37

Japan Flutists Association, Tokyo Juni 2011, S. 37–41

Cooper, Albert: Gadget Page [Open or closed G sharp flute?]. In: Pan, Dezember 1983, S. 6

Giannini, Tula: An Old Key for a New Flute. The Boehm Flute with closed G sharp: Historical Perspectives. En: The Flutist Quarterly, New York octubrer 1984, p. 15–20

Hünteler, Konrad: Die geschlossene Gis-Klappe. En: Busch-Salmen, G. / Krause-Pichler, A.: Handbuch Querflöte. Instrument, Lehrwerke, Aufführungspraxis, Musik, Ausbildung, Beruf. Kassel 1999, p. 40–41

Lawrence, Eleanor: Re-evaluating the G sharp Key: An Introduction. En: The Flutist Quarterly, New York octubre 1984, p. 6–7, 10–12

Lawrence, E. / Schultz, P.: Facts and Figures on Open G sharp Flutes. En: The Flutist Quarterly, New York octubre 1984, p. 23.

Minzloff, Oliver: In Commemoration of Theobald Boehm’s 190th Anniversary, April 9, 1794. Open G sharp? Gee Whiz! En: The Flutist Quarterly, New York octubre 1984, p. 21–22; Flöte aktuell, Frankfurt am Main febrero 1987, p. 19–22

Pailthorpe, Daniel: Why I play Open G sharp. En: Pan, London diciembre 1997, p. 14–16

Sachs, Gerhard: Offenes gis – geschlossenes gis auf der Böhmflöte. Akustische Betrachtungen. En: Flöte aktuell, Frankfurt am Main febrero 1987, p. 19

Ventzke, Karl: Die Gis-Klappe bei der Boehmflöte. En: Instrumentenbau-Zeitschrift, Siegburg abril 1960, p. 205–206

Vogt, Linda: Bygone Flute Systems and the Flutists who played them in Australia. En: Flute Australia, Sydney mayo 1996, p. 6–8

Wimberly, David: Letter to the Editor. En: The Flutist Quarterly, New York marzo 1985, p. 3.

Wimberly, David: Alexander Murray: Vision Quest. En: The Flutist Quarterly, New York junio 1985, p. 48–51

El flautista Konrad Hünteler defiende su cambio de la llave de Sol sostenido cerrada a la de Sol sostenido abierta y rechaza la llave cerrada decididamente.

Según Lawrence/Schultz, numerosos constructores de flauta como Lamberson, Powell y Selmer reconocen la superioridad de la llave de Sol# abierta, pero solo construyen unas pocas flautas con Sol sostenido abierta, a causa de la escasa demanda.

Dayton C. Miller escribe en su comentario que cambió después de un profundo examen de todas clases de la llave de Sol sostenido a la llave abierta y recomienda a todos los principiantes comenzar con ella.

El flautista Oliver Minzloff, que vive en Basilea y cambió también a la llave Sol sostenido abierta, relata un ensayo con ocho principiantes de flauta, de los cuales los cuatro que empezaron con la llave de Sol sostenido abierta, ya pudieron tocar bien tras seis meses, mientras que los cuatro que empezaron con Sol sostenido cerrada, después de un año y medio continuaban teniendo problemas con el movimiento contrario del dedo de Sol sostenido Como otras desventajas de la llave de Sol sostenido cerrada dice que el dedo meñique solo se mueve en 5 de 40 tonalidades y por eso queda desentrenado (en Sol sostenido abierta 22 veces), que el Mi 3 está demasiado alto y que la mecánica de Mi produce nuevos problemas.

El constructor de flautas Gerhard Sachs sobre todo indica las desventajas acústicas de la llave de Sol sostenido cerrada. Además de la mecánica de Mi desventajosa, la chimenea del agujero adicional extiende el tubo y hace el tono más bajo. Por el agujero de Sol sostenido adicional, el Re# 3 se hace frecuentemente demasiado alto y el color de la nota del Sol sostenido cerrada es diferente al de las notas Si bemol, La o Sol.

David Wimberly informa en su carta al editor que Jack Moore y él construyeron unas 80 flautas con Sol sostenido abierta y las vendieron en la mayoría de los casos en los Estados Unidos y que numerosos flautistas le confirmaron que sentían la llave de Sol sostenido abierta después de un tiempo de cambio de casi tres meses como mucho más cómodo y lógico que la llave de Sol sostenido cerrada. Según David Wimberly, la llave de Sol sostenido cerrada es inferior a la llave de Sol sostenido abierta en las tres octavas, los rellenos y las fijaciones son menos sólidos. Wimberly describe en su artículo el nuevo modelo de la llamada “flauta Murray”, construido en 1985, que ofrece además de una llave de Sol# abierta, algunas otras peculiaridades como una llave de Re sostenido abierta.

Las fotos son de mi “Verzeichnis der erhaltenen Flöten von Theobald Böhm / Catálogo de las flautas conservadas de Theobald Böhm“.

1 Sol sostenido cerrada, flauta cónica de vieja construcción de Theobald Böhm (Munich, Deutsches Museum 2009-150)

2 Sol sostenido abierta, flauta cónica con anillos de Theobald Böhm (Frankfurt am Main, colección privada 83125)

3 Sol sostenido abierta, flauta cilíndrica no. 30 de Theobald Böhm (Munich, Deutsches Museum 2009-156)

4 Sol sostenido abierta, flauta cilíndrica de Theobald Böhm, sistema 1854 (Frankfurt am Main, colección privada 85068)

5 Sol sostenido abierta, flauta cilíndrica de Böhm & Mendler, madera adelgazada con chimineas de los agujeros de tono elevadas (Washington, Library of Congress Miller 306)

6 Sol sostenido cerrada, flauta cilíndrica de Böhm & Mendler, llave Dorus modificada sin agujero Sol sostenido adicional. La llave Sol sostenido es abierta en reposo (Frankfurt am Main, colección privada 86590)

7 Sol sostenido cerrada, flauta cilíndrica de Böhm & Mendler, llave Böhm Sol sostenido sin agujero Sol sostenido adicional. La llave Sol sostenido es cerrada en reposo. Flauta de Macauley con plaquitas de oro (Washington, Library of Congress Miller 161)

8 Sol sostenido cerrada, flauta cilíndrica de Böhm & Mendler, con agujero adicional a la parte revés (Stuttgart, colección privada)

Рассуждения Теобальда Бёма об открытом и закрытом соль-диезе

от Людвиг Бём (2014)

Результатом моих поисков, а, в частности, моих объявлений в музыкальных журналах, явились нашедшиеся в Швеции в 1981 году письма Теобальда Бёма к Вильгельму Поппу, которые сейчас находятся в городском архиве г. Мюнхена. Письмо, написаное 5. 2. 1865 г., было посвящено теме открытого и закрытого соль-диез клапана. К письму также была приложена короткая версия статьи Бёма об открытом соль-диезе. Вскоре им был написан полный вариант этой статьи, который существует как черновик в Баварской государственной библиотеке в Мюнхене и как оригинал в Библиотеке Конгресса в Вашингтоне. Бём сам перевёл статью на английский и французский языки. Статья не была опубликована, но её содержание Бём использовал в книге „Флейта и акустические, технические и творческие аспекты игры на ней“ Мюнхен 1871г. стр. 20–22.

1) Письмо Теобальда Бёма к Вильгельму Поппу

Мюнхен 5 февраля 1865г.

Уважаемый господин Попп,

Вы были правы, предпочитая мою флейту, а не флейту Лота из Парижа, хотя значение созданной мною системы клапанов и было принижено первым флейтистом Парижа Дорусом из–за его предположительных улучшений закрытого соль-диез клапана в акустическом и механическом плане. После долгих размышлений я создал систему клапанов с открытым соль-диезом, в которой все клапаны помогают естественному движению пальцев вверх и вниз. Дорус надеялся, что его новшества сделают флейту более доступной для тех, кто играл на старых флейтах, но не подумал о том, что недостатков будет больше, чем преимуществ.

Лот соединил для него соль-диез и ля клапаны так, что при нажатии безымянным пальцем левой руки, как на старых флейтах, звучало соль, а при нажатии мизинцем – соль-диез. В моей системе звучит соль при нажатии мизинцем, а соль-диез при поднятии мизинца. Я это сделал после долгих раздумий, и каждый, кто задумается над этим, согласится со мной.

Когда я объяснил всё это Дорусу, он согласился, что сделал глупость, а я сделал глупость и из уважения к нему не опубликовал всё о недостатках закрытого соль-диеза. Дорус был в это время первым флейтистом в Париже, и все его ученики играли на таких флейтах, как и он. Многие из них впоследствии перешли на открытый соль-диез. Де Вройе сказал мне, когда я ему всё объяснил, что он мне сочувствует, но ничего не может изменить, так как потребуется много времени для изучения новой системы. И поскольку Де Вройе будет продавать в Германии флейты с закрытым соль-диезом, так как Лот ему больше платит, чем я, то я вынужден буду всё опубликовать. До этого момента я не считал нужным это делать, потому что в Германии, Англии, России и почти везде, кроме Франции, все и так играют пo моей системе. На приложенных страницах я объясню все преимущества и недостатки, и вы со мной согласитесь.

Преданный Вам

Теобальд Бём

2 Статья Теобальда Бёма (Вашингтонская версия) Комментарии об изменениях в системе клапанов “Флейты Бёма“, сделанных в Париже

Требования, предъявляемые к хорошей флейте – это акустическое совершенство звука и интонации, лёгкость игры и простота механики. Вопрос, который интересует тех, кто уже играет на флейте, и тех, кто хочет научиться на ней играть, какая система лучше, с открытым или закрытым соль-диезом?

1. Акустические свойства инструмента

Соединение закрытого соль-диез клапана с открытостоящим клапаном ля не позволяет девятому отверстию под клапаном ля быть самостоятельно открытым, а отверстие под соль-диезом слишком низко на флейте, чтобы быть резонатором для ми третьей октавы. Поэтому эта нота не берётся так легко и уверенно, как на моей флейте с открытым соль-диезом. Есть также разница в артикуляции в пиано и в интервалах, например, между соль-диезом и ля второй, или ми третьей октавы.

2. Лёгкость игры

Вышеназванное соединение двух клапанов усложняет игру по двум причинам: для закрытого соль-диез клапана нужна сильная пружина, поэтому пальцам левой руки приходится с удвоенной силой преодолевать сопротивление ля и соль-диез клапанов. Игра этим усложняется, особенно при трелях соль-диез – ля; ля-бемоль – си-бемоль и ре-диез – ми третьей октавы.

Далее нужно отметить, что мизинец левой руки движется в противоположную сторону с пальцами правой руки. Несомненно, синхронные движения пальцев обеих рук в одну сторону, как при открытом соль-диезе, проще, чем движения в разные стороны.

На возражение, что мизинец левой руки нужен не в каждой тональности, замечу, что в наше время каждый хороший флейтист должен уметь играть во всех тональностях. А так как соль-диез или ля-бемоль присутствуют в шестнадцати из двадцати четырёх тональностей, то мизинец левой руки должен быть также тренирован, как и другие пальцы.

3. Простота механики клапанов

Чем сложней механика клапанов и чем чаще она используется, тем сложней приводить её в порядок. Невозможностью закрыть 11 отверстий 9 пальцами объясняются соединения клапанов у фа-диеза и си-бемоля в моей системе. Поскольку мизинец левой руки ответственнен только за соль-диез клапан, то не было необходимости создавать ещё третье сложное соединение клапанов, которое бы только повредило акустике и простоте использования механизма. Утверждение, что закрытый соль-диез облегчает изучение новой флейты тем, кто играл на старой, это заблуждение. Многим пожилым флейтистам было достаточно нескольких недель занятий, чтобы снова начать играть, и многие известные солисты, поменявшие по моему совету закрытый соль-диез на открытый, убедились в преимуществах моей системы. А то, что в Париже и в других местах известные солисты играют на флейтах с закрытым соль-диезом показывает, что сложности можно преодолеть с помощью таланта и усердия. Но это не доказывает, что эти флейтисты не достигли бы больших успехов меньшими силами с открытым соль-диезом.

Создавая мою систему, я долго размышлял, взвешивал и проверял всё, чтобы выбрать всё самое лучшее. Поэтому я готов принять конструктивную критику и предложения по улучшению.

Комментарии

Теобальд Бём называет в своём письме две причины, по которым он раньше не высказывался открыто против закрытого соль-диез клапана. Во-первых, Бём очень уважал Луи Доруса, который сменил Жан-Луи Тулу в Парижской консерватории и который первым в 1837 году начал играть на флейте Бёма. Луи Лот сменил для него в 1838 году открытый соль-диез на закрытый. (Вельх, Кристоф. История флейты Бёма. Лондон 3 издание 1896 г. стр. 58). Бём посвятил Дорусу в 1845 году свой опус № 24, в 1848 году французский перевод своего сочинения „Создание флейт и их новейшие усовершенствования“, а также в 1857 году свой опус № 35. В письме своему ученику Себастьяну Отту от 3. 2. 1869 г. он называет Доруса лучшим флейтистом в мире (Библиотека Конгресса. Вашингтон. Коллекция Миллера).

Во-вторых, в этот момент он не считал нужным открыто выступать против системы закрытого соль-диеза, так как за исключением Франции все играли на флейтах с открытым соль-диезом. Не была исключением и Америка. 29. 11. 1854 г. в Америку была выслана флейта Бёма № 85 для флейтиста Филиппа Эрнста из Нью-Йорка (Документация мастерской Бёма в Мюнхене 1847–1859; 1876–1879 г. г. Библиотека конгресса. Вашингтон. Коллекция Миллера). В 1864 г. в Америке с триумфом выступил флейтист Мартин Хейндл, играющий на флейте под номером 19. Теобальд Бём писал в письме своему другу Вальтеру С. Броадворду: „С момента выступления в Америке моего бывшего ученика Хэйндла у меня больше заказов из Америки, чем я могу исполнить. И хотя я предлагал им флейты моего друга Лота из Парижа, люди ждут мои флейты.“

Почти все флейты из мастерской Бёма (1828–1839), Бёма и Греве (1839–1847), Бёма (1847–1861), и Бёма и Мендлера (1862–1888) сделаны с открытым соль-диезом. В редких случаях, если заказчик настаивал, Бём делал вопреки своим убеждениям и очень неохотно флейты с закрытым соль-диезом. Согласно его бухгалтерским книгам , между 1847 и 1859 г. г. были сделаны 128 флейт с открытым и только 2 (№3 и №22) с закрытым соль-диезом. А также почти все последующие флейты были с открытым соль-диезом.

В наше время, за исключением России и стран бывшего Советского Союза, преобладает система закрытого соль-диеза, хотя некоторые выдающиеся флейтисты играют на флейтах с оригинальной системой Бёма с открытым соль-диезом: например, Вильям Беннетт в Лондоне и Денис Буряков в Нью-Йорке.

Literature

Boehm, Th. / Miller, D. C., The Flute and Flute Playing, 1922, p. 71

Böhm, Ludwig: Theobald Böhms Stellungnahme zur geschlossenen Gis-Klappe

In:

Japan Flutists Association, Tokyo 20. 2. 1984, S. 17–19

Das Musikinstrument, Frankfurt am Main April 1984, S. 54–57

Fomrhi Quarterly, Oxford April 1984, S. 44–47

The Washington Flute Scene, Washington Juni/Juli 1984, S. 3–6

Glareana, Zürich Juli 1984, S. 16–19

Tibia, Celle Oktober 1984, S. 206–209

The Flutist Quarterly, New York November 1984, S. 8 f.

Flöte aktuell, Frankfurt am Main Februar 1987, S. 22 (gekürzt)

Newsletter of the Australian Flute Association, Sydney Februar 1987, S. 5 f.; Mai 1987, S. 6 f.; August 1987, S. 6 f.

South Australian Flute News, Adelaide Februar 1987, S. 22–25

The Flute, Sydney November 1987, S. 12–14

Pan, London Dezember 1987, S. 19–22

Huilisti, Tampere Dezember 1989, S. 14–19

Journal Traversières, Lyon März 1990, S. 16–19

New Zealand Flute Society News, Christchurch September 1990, S. 29–34

Böhm, Ludwig: Festschrift zum 200. Geburtstag von Theobald Böhm. München 1994, S. 38–40

South Australian Flute News, Adelaide Juli 1994, S. 20–22

The Flute, Sydney November 1994, S. 42–44

Traversières Magazine, Paris Januar 2007, S. 58–60

Fluit, Amsterdam Januar 2007, S. 31–37

Japan Flutists Association, Tokyo Juni 2011, S. 37–41

Cooper, Albert: Gadget Page [Open or closed G sharp flute?]. In: Pan, Dezember 1983, S. 6

Giannini, Tula: An Old Key for a New Flute. The Boehm Flute with closed G sharp: Historical Perspectives. In: The Flutist Quarterly, New York October 1984, p. 15–20

Hünteler, Konrad: Die geschlossene Gis-Klappe. In: Busch-Salmen, G. / Krause-Pichler, A.: Handbuch Querflöte. Instrument, Lehrwerke, Aufführungspraxis, Musik, Ausbildung, Beruf. Kassel 1999, p. 40–41

Lawrence, Eleanor: Re-evaluating the G sharp Key: An Introduction. In: The Flutist Quarterly, New York October 1984, p. 6–7, 10–12

Lawrence, E. / Schultz, P.: Facts and Figures on Open G sharp Flutes. In: The Flutist Quarterly, New York Oktober 1984, p. 23.

Minzloff, Oliver: In Commemoration of Theobald Boehm’s 190th Anniversary, April 9, 1794. Open G sharp? Gee Whiz! In: The Flutist Quarterly, New York October 1984, p. 21–22. Flöte aktuell, Frankfurt am Main February 1987, p. 19–22

Pailthorpe, Daniel: Why I play Open G sharp. In: Pan, London December 1997, p. 14–16

Sachs, Gerhard: Offenes gis – geschlossenes gis auf der Böhmflöte. Akustische Betrachtungen. In: Flöte aktuell, Frankfurt am Main February 1987, p. 19

Ventzke, Karl: Die Gis-Klappe bei der Boehmflöte. In: Instrumentenbau-Zeitschrift, Siegburg April 1960, p. 205–206

Vogt, Linda: Bygone Flute Systems and the Flutists who played them in Australia. In: Flute Australia, Sydney May 1996, p. 6–8

Wimberly, David: Letter to the Editor. In: The Flutist Quarterly, New York March 1985, p. 3.

Wimberly, David: Alexander Murray: Vision Quest. In: The Flutist Quarterly, New York June 1985, p. 48–51

В своей книге Конрад Хюнтеле описывает свой переход с закрытого на открытый соль-диез и своё отрицательное отношение к закрытому соль-диезу.

В книге Лоренца/Шульца упоминаются такие мастера, как Ламберсон, Пауелл и Сельмер, которые признают преимущества открытого соль-диеза, но не производят флейты с ним, так как на них нет спроса.

Дейтон С. Миллер описывает свой переход на открытый соль-диез после долгих размышлений и советует начинающим флейтистам делать тоже самое.

Живущий в Базеле флейтист Оливер Минцлофф, тоже перешедший на открытый соль-диез, рассказывает об эксперименте с 8 флейтистами, из которых 4 начинали учиться на открытом соль-диезе и за 6 месяцев научились достаточно хорошо играть. Тогда как остальные, играющие на закрытом соль-диезе, и после полутора лет занятий сталкивались с проблемами при противоположном движении мизинца. В числе недостатков он называет также то, что при закрытом соль-диезе мизинец движется только при 5 из 40 нот, а при открытом – при 22, и поэтому он лучше натренирован, а также то, что ми третьей октавы слишком высокое, а ми – механика создаёт новые проблемы.

Мастер Герхард Закс указывает на акустические недостатки закрытого соль-диеза, недостатки ми-механики, проблемы с интонацией ре-диез третьей октавы а также звуковые недостатки си-бемоля, ля и соль.

Давид Уимберли рассказывает в своём письме о том, что он с Джеком Моором изготовил 80 флейт с открытым соль-диезом и продал их в Америку. Флейтисты, переучившиеся на открытый соль-диез подтвердили, что они воспринимали эту систему как более логичную и удобную, а также акустически лучшую. Он также описывает созданную ими так называемую „Мюррей-флейту“ с открытым соль-диезом и открытым ре-диезом.

Фотографии взяты из моего „каталога сохранившихся флейт Теобальда Бема / Catalogue of the still existing Flutes of Theobald Böhm“.

1 Закрытый соль диез клапан, коническая флейта старого образца Теобальда Бема (Мюнхен, Немецкий музей 2009-150)

2 Открытый соль диез клапан, коническая флейта с кольцами Теобальда Бема (Франкфурт на Майне, Частная коллекция 83125)

3 Открытый соль диез клапан, цилиндрическая флейта под номером 30 Теобальда Бема (Мюнхен, Немецкий музей 2009-156)

4 Открытый соль диез клапан, цилиндрическая флейта Теобалда Бема, система 1854 (Франкфурт на Майне, Частная коллекция 85068)

5 Открытый соль диез клапан, цилиндрическая флейта Бем & Мендлер, с уменьшенной толщиной деревянного тела и повышенным камином отверстий (Вашингтон, Библиотека Конгресса, Миллер 306)

6 Закрытый соль диез клапан, цилиндрическая флейта Бем & Мендлер, видоизменённый соль диез клапан Доруса без дополнительного соль диез отверстия. Соль диез клапан открыт в состоянии покоя (Франкфурт на Майне, Частная коллекция 86590)

7 Закрытый соль диез клапан, цилиндрическая флейта Бем & Мендлер, соль диез клапан Бема без дополнительного соль диез клапана. Соль диез клапан в состоянии покоя закрыт. Флейта Маколей с золотыми пластинами (Вашингтон, Библиотека Конгресса, Миллер 161)

8 Закрытый соль диез клапан, цилиндрическая флейта Бем & Мендлер, с дополнительным соль диез отверстием в нижней части флейты (Штутгарт, частная коллекция)

Flautists, who are alive and only play or played the original Böhm system with open G sharp key

(not the French variant with closed G sharp key)

by Ludwig Böhm (1 February 2024)

1) Germany

Bad König: Gottfried Schwarz, ex Bergische Symphoniker

Berlin: Blanka Sedlmayr, Konzerthausorchester

Bochum: Sabine Koeser, ex Folkwang Musikschule Essen

Bretten (bei Karlsruhe): Laura Paulu, Musikschule Bretten

Bühlertann (bei Heilbronn): Victor Wulf, Musikschule Heubach

Chemnitz: Katharina Böhm, Leipziger Symphonieorchester

Darmstadt: Danielle Schwarz, Staatsorchester Darmstadt

Dießen: Albert Müller, ex Münchner Philharmoniker

Dresden: Raschid Gimaletdinow, ex Stadttheater Döbeln, Musikschule Freital

Essen: Lesley Olson, Folkwang Universität der Künste

Frankfurt am Main:

Vladislav Brunner, Hochschule für Musik Würzburg

Katerina Polishchuk

Freiburg im Breisgau: Hartmut Gerhold

Gauting: Wolfgang Haag, ex Bayerisches Staatsorchester

Karlsruhe: Heike Nicodemus, Hochschule für Musik Karlsruhe

Krailling: Carla Maria Walchner, ex Orchester des Staatstheaters am Gärtnerplatz

Langenfeld (bei Düsseldorf): Boris Boltianski

Lenzkirch (bei Titisee): Leontine Jortzig von Türckheim

München:

Tobias Kaiser, Ensemble Zeitsprung und Arte Viva

Fritz Mimietz, ex Münchner Rundfunkorchester

Peter Ruppert, ex Bayerisches Staatsorchester

Münster: Konrad Hünteler, ex Hochschule für Musik und Theater Münster

Neuenstadt (bei Heilbronn): Christiane Lamb

Reutlingen:

Birgit Aicheler

Birgitt Metzner-Zell

Tübingen: Ursula Pešek

Utting am Ammersee: Christof Fiedler

Weimar: Kirill Mikhailov, Staatskapelle Weimar

Wuppertal: Richard Schwarz

2) Europe

Armenia

Yerevan: Vicka Aghazaryan

Belarus

Grodno:

Alla Golub, Grodno Music School

Aleksej Sherbo, ex Chamber Orchestra of the Republic of Belarus

Linovo (Pruzhany District): Elena Suprun, Linovskaya Children’s School of Arts

Minsk:

Sergey Balyko, Belarusian Philharmonic Symphony Orchestra

Nadezhda Dashdorzh

Svetlana Gaveilenko, Musical School No. 9

Valery Grigoriev, Belarusian Academy of Music, Piccolo, State Academic Symphony Orchestra

Tatsiana Hlushankova

Larisa Lazotskaya, National Academic Bolshoi Opera and Ballet Theatre Orchestra

Elena Makarevich, Music School

Nikolai Molodov, ex piccolo National Academic Bolshoi Opera and Ballet Theatre Orchestra

Ivan Pleshkevich, ex Opera Orchestra

Julia Olegovna Pripeteni, Music School

Viacheslav Pomozov, Music School

Slava Radkevich, ex National Academic Opera and Ballet Theatre Orchestra of Belarus

Svetlana Shchutskaya, Gymnasium No. 12

Svetlana Situikova, Belarusian Academy of Music

Pavel Suragin, Kids Ensemble of Recorders “Brevis”

Valentin Tichevich, Belarusian Philharmonic Symphony Orchestra

Ekaterina Tolkacheva, Children’s Music School No. 14

Larysa Umerencova, Music School No. 10

Dmitry Vladimirovich Ushakevich, Radio and Television Orchestra

Podsvilye: Elena Meleshko, Podsvilsky Children’s School of Arts

Shumilino: Inna Vorsa, Shumilinskaya Children’s School of Arts

Vitebsk:

Inna Minenkova, A. S. Pushkin Gymnasium No. 3

Svetlana Prokopyuk, A. V. Bogatyrev Children’s Art School

Czech Republic

Olmütz: Hana Čermáková, Conservatory Olomouc

Pardubitz: Jaromír Hönig, ex Conservatory Pardubice

Prague:

František Čech, ex Prague Conservatory

František Čech jr.

Martin Čech

Dana Čechova-Tarabova, Prague Film Symphony Orchestra

M. Henkl, ex Prague State Opera Orchestra

Martin Hlavsa, Prague National Theatre Orchestra

Tomáš Kalous, Prague National Theatre Orchestra

Anna Kostohryzová, ex Prague Radio Symphony Orchestra

Václav Lenc, Prague State Opera Orchestra

Jiři Loukota, Prague State Opera Orchestra

Mario Mesany, Prague Radio Symphony Orchestra

Václav Michálek, ex Prague Symphony Orchestra

Libor Mihule, ex Prague National Theatre Orchestra

Karel Novotný, ex Czech Philharmonic Orchestra

Tomás Pelikán, Music School Vrané nad Vltavov

Estonia

Narva: Larisa Matveeva, Music School

Tallin: Oksana Sinkova, Academy of Music and Theatre

Finland

Vantaa: Kati Fehér

France

Apt (bei Avignon): Thierry Bois

Le Boulou (bei Perpignan): Michel Clergue, ex Conservatoire d’Avignon Perpignan

Montpellier: Michel Rayni, Orchestre de Montpellier

Port de Bouc (bei Marseille): Magali Fabre

Great Britain

Aberdeen:

Anna Kurpanik

Natalia Kurpanik

Bath: Richard Dobson, Bath University

Birmingham:

John Bowler, ex piccolo Royal Opera House Orchestra

Judith Hall, Royal Birmingham Conservatoire

Colchester: Bruce Martin

Leicester: Jenny Brooks

London:

Michie Bennett, ex Royal Academy of Music

William Bennett, Royal Academy of Music

Keith Bragg, Royal Academy of Music, piccolo, Philharmonia Orchestra London

Elmer Cole, ex English National Opera Orchestra

David Evans

Simon Hunt

Tomoka Mukai, BBC Symphony Orchestra

Alexander Murray, ex University of Illinois

Frank Nolan, ex Piccolo, London Symphony Orchestra

Daniel Pailthorpe, BBC Symphony Orchestra

Carla Rees, Royal Holloway, University of London

Tom Sargéaunt, Flötenreparatur

Clare Southworth, Royal Academy of Music

Elizabeth Walker

Manchester:

Richard Davis, BBC Philharmonic Orchestra

Rachel Holt

Newcastle: David Haslam, Northern Symphonia

Tonbridge: Pat Daniels

Welwyn: Hannah Lang, ex editor of Pan

Italy

Montescudaio: Georg Kaiser, ex Deutsche Oper Berlin

Sesto San Giovanni (Milano): Gianluigi Nuccini

Latvia

Liepāja: Reinis Lapa, Liepāja Symphony Orchestra

Riga:

Liene Denisjuka-Straupe

Liene Dobičina

Inga Grīnvalde

Guntars Gritāns

Eglė Juciūtė

Alisa Klimanska

Dita Krenberga, Latvian National Symphony Orchestra

Iveta Lāriņa

Ilona Meija, Sinfonietta Riga

Evija Mundeciema, Latvian National Symphony Orchestra

Ieva Pudāne, Sinfonietta Riga

Mareks Romanovskis, Latvian National Armed Forces Orchestra

Imants Sneibis, Latvian Academy of Music

Ligita Spūle, Latvian National Opera Orchestra

Daina Svabe

Ilze Urbāne, Latvian National Symphony Orchestra

Miks Vilsons, Latvian National Opera Orchestra

Aiva Zauberga, Latvian National Symphony Orchestra

Scriveri: Juris Gailītis

Lithuania

Kaunas:

Vida Adomaviciene, Kaunas Petrauskas Music School

Monika Ryškutė

Onute Užameckienė, ex Kaunas State Musical Theatre

Klaipeda:

Rimas Giedraitis, Klaipeda State Music Theatre Orchestra

Vilma Ragaišienė, Klaipeda State Music Theatre Orchestra

Vilnius:

Giedrius Gelgotas, Lithuanian Opera and Ballet Theatre Orchestra

Valentinas Gelgotas, Lithuanian National Symphony Orchestra

Vytenis Giknius, piccolo, Lithuanian State Orchestra

Vytenis Gurstis Lithuanian Opera and Ballet Theatre Orchestra

Mindaugas Juozapaitis, Lithuanian State Orchestra

Aleksandr Oguretzkiy, Music School

Virgis Skudas, Trimitas State Wind Orchestra

Vytautas Sriubikis, Lithuanian Opera and Ballet Theatre Orchestra

Daiva Tumėnaitė, Ensemble “Musica Humana”

Violetas Višinskas, ex Lithuanian National Symphony Orchestra

Algirdas Vizgirda, Lithuanian Academy of Music

Ruta Zubriene, Trimitas State Wind Orchestra

Luxembourg

Luxembourg: Agnese Nikolovska, Conservatoire de Luxembourg

Moldavia

Chisinau: Natalia Sleptova

Netherlands

Amsterdam:

Anne La Berge